The following transcription is the P.E.I. portion of the book, "British America", by John M'Gregor [View DCB Biography]. Published 1832 by William Blackwood, Edinburgh; and T. Cadell, Strand, London. This page is optimized for viewing in 1024x768 pixels and greater.

Transcribed by Brian Molyneaux - [email protected]

BRITISH AMERICA

By JOHN M’GREGOR, Esq.

In Two Volumes.

Vol. I.

William Blackwood, Edinburgh; and T. Cadell, Strand, London.

MDCCCXXXII

To

HIS MOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY,

WILLIAM THE FOURTH.

SIRE,

Your Majesty having been the only British Monarch who ever visited that interesting portion of the Empire which I have attempted to describe, I was emboldened to solicit your Majesty’s Patronage for my Work. For the gracious manner in which permission was granted me to dedicate my humble labours to your Majesty, I beg to offer my very grateful and respectful thanks.

I have the honour to be,

SIRE,

Your Majesty’s

Very dutiful and very loyal Subject,John M’Gregor.

Botanic View, Near Liverpool,

2d January, 1832

[283]

BOOK IV.

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND.

-------------

CHAPTER 1.

Geographical Position of Prince Edward Island – General Aspect of the Country – Counties, and Lesser Divisions – Descriptions of Charlotte Town and the Principle Settlements.

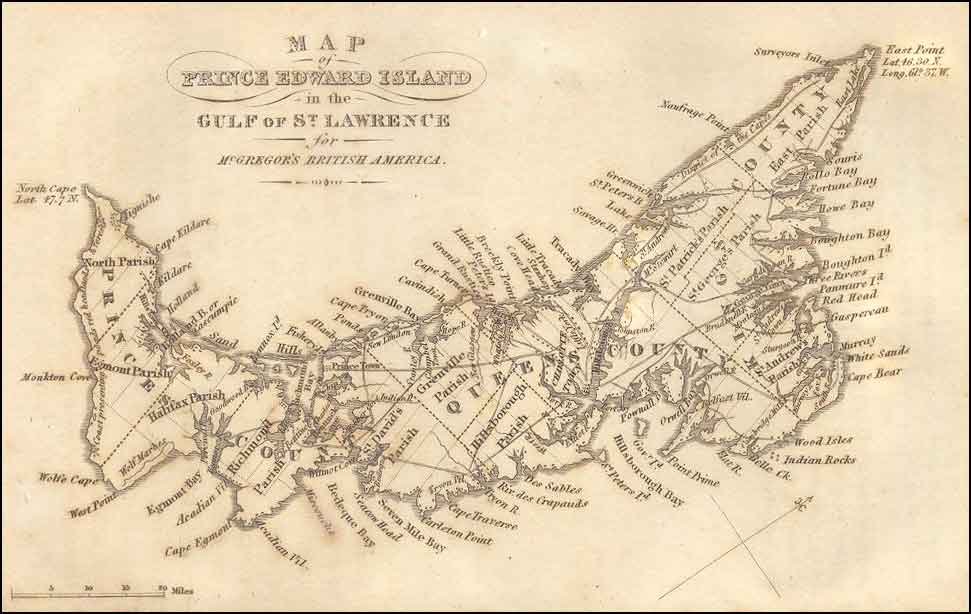

Prince Edward Island is situated in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, within the latitudes of 46° and 47° 10’ N., and longitudes of 62° and 65° W. Its length, following a course through the centre of the island, is 140 miles; and its greatest breadth, thirty-four miles. It is separated from Nova Scotia by Northumberland Strait, which is only nine miles broad, between Cape Traverse and Cape Tormentine. Cape Breton lies within twenty-seven miles of the east point; and Cape Ray, the nearest point of Newfoundland, is 125 miles distant. The distances from Charlotte Town to the following places, are – to the Land’s End, England, 2280 miles; to St. John’s, New Brunswick, by sea, 360 miles, and across the peninsula of Nova Scotia, 135 miles; to Quebec, 580 miles; to Halifax, through the

[284]

Gut of Canso, 240 miles, and by Pictou, 140 miles; to Miramichi, 120 miles; to Pictou, 40 miles.

In coming within view of Prince Edward Island, its aspect is that of a level country, covered to the water’s edge with trees, and the outline of its surface scarcely curved with the appearance of hills. On approaching nearer, and sailing round its shores, (especially on the north side,) the prospect becomes interesting, and presents small villages, cleared farms, red headlands, bays, and rivers which pierce the country; sandhills covered with grass; a gentle diversity of hill and dale, which the cleared parts open to view, and the undulation of surface occasioned by small lakes or ponds, which from the sea appear like so many valleys.

On landing and traveling through the country, its varied, though not highly romantic scenery, and its agricultural and other improvements, attract the attention of all who possess a taste for rural beauties. Owing to the manner in which it is intersected by various branches of the sea, there is no part at a greater distance from the ebbing and flowing of the tide than eight miles.

It abounds with streams and springs of the purest water; and it is remarked, that in digging wells, no instance of being disappointed in meeting with good water has occurred. There are no mountains in the island A chain of hills intersects the country between Disable and Grenville Bay; and, in different parts, the lands rise to moderate heights; but, in general, the surface of the island may be considered as devia-

[285]

ting no more from the level than could be wished, for the purpose of agriculture.

Almost every part affords agreeable prospects and beautiful situations. In summer and autumn, the forests exhibit a rich and splendid foliage, varying from the deep green of fir, to the lively tints of the birch and maple; and the character of the scenery at these seasons, displays a smiling loveliness and teeming fertility.

The island is divided into three counties, these again into parishes, and the whole subdivided into sixty-seven townships, containing about 20,000 acres each. The plot of a town, containing about 400 building lots, and the same number of pasture lots, are reserved in each county. These are, George Town, in King’s County; Charlotte Town, in Queen’s County; and Prince Town, in Prince County.

Charlotte Town, the seat of government, is situated on the north bank of Hillsborough river, near its confluence with the rivers Elliot and York. Its harbour is considered one of the best in the Gulf of St Lawrence. The passage into it leads from Northumberland Strait, to the west of Point Prime, between St Peter’s and Governor’s Islands, up Hillsborough Bay, to the entrance of the harbour. Here its breadth is little more than half a mile, within which it widens, and forms a safe, capacious basin, and then branches into three beautiful and navigable rivers. The harbour is commanded by different situations that might easily be fortified, so as to defend the town against any ordinary attack by water. At present, there is a

[286]

battery in front of the town, near the barracks; another on Farming Bank; and a block house, with some cannon, at the western point of the entrance.

Charlotte Town stands on ground which rises in gentle heights from the banks of the river, and contains about 350 dwelling-houses, and about 3400 inhabitants. The plan of the town is regular; the streets broad, and intersecting each other at right angles; five or six vacancies are reserved for squares; and many of the houses lately built are finished in a handsome style, and have a lively and pleasing appearance. The court-house – in which the Courts of Chancery, as well as the Court of Judicature, are held, and in which the Legislative Assembly also sit – The Episcopal church, the New Scotch church, and the Catholic and Methodist chapels, are the only public buildings. The barracks are pleasantly situated near the water, and a neat parade or square occupies the space between those of the officers and privates. The building lots are eighty-four feet in front, and run back 160 feet. To each of these a pasture-lot of twelve acres was attached in the original grants; and there was formerly a common, lying between the town and pasture-lots, which, however, the Lieutenant-Governor Fanning found convenient to grant away in lots to various individuals.

On entering and sailing up the harbour, Charlotte Town appears to much advantage, with a clean, lively, and prepossessing aspect, and much larger than it in reality is. This deception arises from its occupying

[287]

an extensive surface in proportion to the number of houses, to most of which large gardens are attached.

Few places offer more agreeable walks, or prettier situations, than those in the vicinity of Charlotte Town. Among the latter, Spring Park, St Avard’s, the seat of the Attorney-General, Mr Johnston; Fanning Bank, on which his excellency Governor Ready has made great improvements, and some farms lying between the town and York river, are conspicuous.

On the west side of the harbour lies the Fort, or Warren, Farm. This is perhaps the most beautiful situation on the island; and the prospect from it embraces a view of Charlotte Town, Hillsborough river for several miles, part of York and Elliot rivers, a great part of Hillsborough Bay, Governor’s Island, and Point Prime. A small valley and pretty rivulet wind through the middle of its extensive clearings; and the face of this charming spot is agreeably varied into gently rising grounds, small vales, and level spaces. When the island was taken, the French had a garrison and extensive improvements in this place; and here the commandant chiefly resided. Afterwards, when the island was divided into townships, and granted away to persons who were considered to have claims on government, this tract was reserved for his majesty’s use. Governor Patterson held possession of it while on the island, and expended a considerable sum in its improvement.

The late Abbé de Calonne (brother to the famous financier) afterwards obtained the use and possession

[288]

of this place, during his residence on the island; and since then, the family of the late General Fanning have by some means obtained a grant of this valuable tract.*

During the summer and autumn months, the view from Charlotte Town is highly interesting. The blue mountains of Nova Scotia appearing in the distance; a long vista of the sea, through the entrance of the harbour, forming, with the basin, and part of Elliot, York, and Hillsborough rivers, a fine branching sheet of water; and the distant farms, partial clearings, grassy glades, intermingled with trees of various kinds, but chiefly the birch, beech, maple, and spruce fir, combine to form a landscape that would please even the most scrupulous of picturesque tourists.

No part of the island could have been more judiciously selected for its metropolis, than that which has been chosen for Charlotte Town; it being situated almost in the centre of the country, and of easy access, either by water, or by the different roads leading to it from the settlements.

*There has been much said about the claim of right to this property; and a wish not to hurt the feelings of private individuals prevents me from detailing particulars contained in original documents which I possess. I will, however, assert, that no grant of this property was made to M. de Calonne; but I believe he was offered it as an asylum for himself and a number of French refugees. He had, however, too much ambition to retreat like a hermit from the great world; and his grand purpose at the time, was to plan and effect a counter revolution in France. I have by me several letters written by his brother the Abbé, while on the island, to official persons there at the same time, which throw much light on this subject.

[289]

George Town, or Three Rivers, is also situated near the junction of three fine rivers, on the southeast part of the island. Very little has been yet done in order to form a town in this place, although it has often been pointed out as better adapted for the seat of government than Charlotte Town. It has certainly a more immediate communication with the ocean, but it is not so conveniently situated for intercourse with many parts of the island. Its excellent harbour, however, and its very desirable situation for the cod and herring fisheries, will probably, at no very distant period, make it a place of considerable importance. It is well calculated for the centre of any trade carried on within the Gulf of St Lawrence. The harbour is not frozen over for some time after all the other harbours in the gulf, and it opens earlier in the spring. A few hours will carry a vessel from it to the Atlantic, through the Gut of Canso; and vessels can lay their course from thence to Three Rivers with a south-west wind, (which prevails in the summer,) which they cannot do to Charlotte Town. This harbour lies also more in the track to Quebec, and other places up the gulf. Its access is safe, having a fine broad and deep entrance, free from sand-bars, or indeed any danger; and can be easily distinguished by two islands, one on each side. Excellent fishing-grounds lie in its vicinity; and herrings enter it in large shoals, early in May. On Saturday evenings, or on Sunday mornings, the Acadian French fishing shallops come in from the fishing-grounds, close to Three Rivers, to pass Sunday within the harbour.

[290]

The entrance to Three Rivers Bay is between Boughton and Panmure islands. A sandy beach connects them with the main. Pilots are ready to attend when a signal is hoisted; and, although the channel is broad, and many masters of large ships venture in with the assistance of sounding, it is as well not to run the risk of grounding on some sandy spits. Within the bay there are several harbours; the best is Montague River.

The settlements contiguous to George Town, on Cardigan, Montague, and Brudnelle rivers, are rapidly extending, and the settlers are directing their attention more to agriculture than formerly. A considerable quantity of timber has, within the last twenty years, been exported from hence; and a number of superior ships have also been built here for the British market. At present, there are two well-established ship-yards, one at Brudnelle Point, where the French, under Count de Raymond, had an extensive fishery, and some hundreds of acres, now overgrown with trees, under cultivation. The other ship-yard is at Cardigan River. Several large and beautiful vessels have been built at each; but the late ruinous depression in the value of shipping has brought the business of constructing vessels here, as elsewhere, to a stand.

The district of country bordering on Three Rivers must, when populously settled, become, if not the first, one of the most important districts in the colony. Its great natural advantages cannot but eventually secure its prosperity.

[291]

Prince Town (or more properly, the point of a peninsula so called) is situated on the south side of Richmond Bay, and on the north side of island. There are no houses, however, erected on the building lots; and the pasture lots have long since been converted to farms, which form a large straggling settlement.

Darnley Basin lies between Prince Town and the point of Allanby, which forms the south side of the entrance to Richmond Bay. Along Allanby Point, and round the basin, a range of excellent farms extends, some of which stretch across the point, and have two water fronts, one on the basin, the other on the gulf shore.

The district of Richmond Bay, called by the French, Malpeque, and still generally known by that name, comprehends a number of settlements, the principal of which (after Prince Town and Darnley Basin) are, Ship-Yard, Indian River, St Eleanor’s, Bentinck River, Grand River, and the village along the township No. 13.

Richmond Bay is ten miles in depth, and nine miles in breadth. The distance across the isthmus, between the head of this bay and Bedeque, on the opposite side of the island, is only one mile.

There are six islands lying within or across the entrance of Richmond Bay; and its shores are indented with numerous coves, creeks, and rivers. It has three entrances formed by the islands, but the easternmost is the only one that will admit shipping. This place is conveniently situated for cod and her-

[292]

ring fisheries, and was resorted to by the New England fishermen before the American Revolution. During the last twenty years, several cargoes of timber have been exported from this port; and a number of ships and brigs have been built here for the English market.

The inhabitants of Richmond Bay are principally Scotch; many of whom, or their parents, emigrated along with Judge Stewart’s family, in 1771, from Cantyre, in Scotland. They retain most of the habits, customs, and superstitions, then prevalent in their native country; so much so, that in mixing with them, I have heard old people, who remembered the amusements common at Christmas, Hallowe’en, and other occasions, fifty years ago, say they could fancy themselves carried back to that period. The old music, the old songs, the old tales of Covenanters and Papistry, the ghost stories of centuries past, are often heard in this district; and I must also add, that I have seen, at the kirk of Prince Town, and in its immediate vicinage, striking delineations of some of the most highly-coloured pictures in the Holy Fair of Burns. I may here observe generally, that customs and manners, which are nearly forgotten in Scotland, have become domiciliated in this district, and in some other parts of the island. There are a few English families, and a great number of Irish, settled among the other inhabitants of Richmond Bay. The Irish settlers were generally employed previously in the Newfoundland fisheries.

At St Eleanor’s there was a popular settlement of

[293]

Acadian French. Some difficulties about the tenures of their lands, occasioned them to abandon the place, and settle in other parts of the island.

The inhabitants of Richmond Bay are, generally speaking, a moral and orderly people. The majority profess the Presbyterian faith; and their clergymen are in connexion with the synod of Pictou. At Prince Town, where the Reverend Mr Keir, a man of exemplary piety and sincerity of character, has officiated for about twenty years, there is a very respectable kirk, and a grammar-school; and there are two other kirks on the opposite side of the bay. At St Eleanor’s, there is a church erected for the Reverend Mr. Jenkins, who has since removed to Charlotte Town. The Scotch Highlanders, and the French Acadians, have also Catholic chapels.

On Lennox Island, within Richmond Bay, the Indians, who are of the once numerous Micmac tribe, and profess the Roman Catholic religion, have a chapel and burying-place. This island, where their chief has a house, is their principle rendezvous; they assemble here about midsummer, on which occasion they meet their priest, or the bishop, who hears confessions, administers baptisms, marries those who are inclined to enter into that state, and makes other regulations for their conduct during the year. After remaining here a few weeks, the greater number resume their accustomed and favourite roving life, and wander along the shores, and through the woods of the neighbouring countries.

Cascumpeque is about sixteen miles north from

[294]

Richmond Bay, and twenty-four miles from the north cape of the island. Its harbour is safe and convenient. The lands are well adapted for agriculture; and this place, by its advantageous situation, is well calculated for extensive fishing establishments. The population consists of Acadian French, and some English families; and the stores, houses, &c., of Mr. Hill, the proprietor of the surrounding valuable and fertile lands, on the beautiful point at the harbour’s entrance, are most conveniently situated for the trade and fisheries of the Gulf of St Lawrence.

New London, or the district of Grenville Bay, includes the settlements round the bay, and on the rivers that fall into it, and those at the ponds, between the harbour and Allanby Point. On the east lies the very pretty settlement called Cavendish. The harbour of New London will not admit vessels requiring more than twelve feet water; otherwise it is safe and convenient. It is formed by a ridge of sandy downs, stretching from Cavendish, four miles across the mouth of Grenville Bay, until it contracts the entrance on the west side to half a mile. The bar is dangerous; several vessels have been lost on it, but the crews have never perished.

Cape Tryon, three miles to the north, shelters the bar during north-westerly winds. The lands on the west side of this harbour have long been cultivated; and formerly there were some extensive establishments erected here for the purposes of carrying on the fisheries, but circumstances occurred which prevented their prosperity.

[295]

The situation and beauty of the lands here, are equal, if not superior, to any spot on this side of the island. I never even fancied a more delightful walk than along the green swards, and among the clumps of wood, that extend from the west side of this harbour to Cape Tyron. The shore is indented with coves and beaches, which are separated again by high perpendicular cliffs. We have also, at the same time, a broad view of the ocean, in all its states of impetuous turbulence, gentle motion, or smooth serenity, and the charming beauty of the country, in the picturesque features of which, woods with luxuriant foliage, cultivated farms, and high sandy downs, covered with green grass, are conspicuous.

Harrington, or Grand Rustico Bay, has two entrances, and a harbour for small brigs and schooners. Here are two villages inhabited by Acadian French. The surrounding parts of the bay, with Whately and Hunter Rivers, have, within the last ten or twelve years, become populously settled, by an acquisition of useful and industrious peasantry from different parts of Scotland. There is an island lying across between the two entrances, part of which is covered with wood, and the rest, about three miles in extent, forms sandy downs, on which grows a sort of strong bent grass. On the west side of the harbour, there are on the point several buildings erected in 1814 by one Le Seur, who called himself a French refugee. He began a fishery, which he carried on until the fall of that year, and then absconded in a schooner, which he had previously purchased, but not paid for.

[296]

He left, very adroitly, several people to whom he was much in debt; but the property he had in this place was, under judicious management, quite sufficient to pay them all. It was never discovered what this man was. Some considered him a spy of Napoleon. He had certainly the talents and address to conceal his own purposes; and his insinuating and genteel manners made him very popular. He even had a commission as captain of the militia given him by the governor.

On Hunter river, which falls into Harrington Bay, a very flourishing settlement, named New Glasgow, was planted in 1819 by Mr Cormack, the Newfoundland traveler. The settlers emigrated from the neighbourhood of Glasgow; and they have made extensive clearings and improvements since they were located.

Brackley is one of the most flourishing and pleasantly situated settlements on the island. It lies between Grand Rustico and Stanhope Cove. The inhabitants, who are in easy circumstances, and have all fine farms, which are their own property, are among the most industrious and exemplary people in the colony. It has a harbour for fishing-boats.

Little Rustico, or Stanhope Cove, is esteemed one of the most beautiful settlements on the island. Its situation is agreeable, and the prospects and exposures of many of the extensive farms is delightful. Its distance from Charlotte Town, by a good road across the island, is only eleven miles. The lands

[297]

are the property of Sir James Montgomery and his brothers. The harbour will only admit small vessels.

The inhabitants, however, are not generally in a thriving condition. The facility of reaching Charlotte Town market, with a few trout or fresh herrings, or a dozen or two of eggs, to buy rum and tea, is usually said, in Charlotte Town, to be the cause of poverty in this settlement. They certainly cannot be selling eggs in Charlotte Town market and cultivating their lands at the same time.

Bedford, or Tracady Bay, is five miles to the eastward of Stanhope Cove. It is a harbour for schooners and small brigs, the entrance to which is strait, and lies at the west end of a narrow ridge of sandhills, which stretch across from the east side of the bay.*

The inhabitants are chiefly Scotch Highlanders, or their descendants; and, having settled many years ago, they are unacquainted with improvements in agriculture, and are still but indifferent farmers. On the west side of the bay, and from that to Stanhope Cove, there was, when the island surrendered in 1759, a dense population. The late Captain Macdonald of Glenalladale removed to this place in 1772, with a

*The entrance to all the harbours on the north side of the island, are either at the end, or through narrow ridges of sandy downs; - thus, the entrances to the harbours of Cascumpeque, New London, Grand Rustico, and Tracady, are at the west end of such ridges; and the other harbours, except that of Richmond Bay, have their entrances through similar downs. Strangers are apt to be deceived when approaching these harbours, as they have a general resemblance. It is therefore advisable to have a pilot.

[298]

colony of Highlanders, who settled round the harbour. The property still belongs to his family.

Savage Harbour lies a few miles to the eastward of Tracady. Its entrance is shallow, and will only admit boats. The lands are tolerable well settled, and the inhabitants are chiefly Highlanders. The distance across the island, between this place and Hillsborough River, is about two miles.

The Lake Settlement, situated between Savage Harbour and St Peter’s, is a pretty, interesting place. The farms have extensive clearings, and front on a pond, or lagoon, which has an outlet to the gulf.

St Peter’s is on the north side of the island, about thirty miles to the eastward of Charlotte Town. Its harbour, owing to a sandy bar across the entrance, will only admit small vessels.* There are a number of settlers on each side of its bay, which is about nine miles long; and the river Morell, falling into it from the south, is a fine rapid stream, frequented annually by salmon. The lands fronting on this bay belong principally to Messrs C. and E. Worrell. They reside on the property, where they are making considerable improvements, and have built granaries,

*A most worthy gentlemen, but ill calculated, however, for a merchant, owned a brig, which he loaded at Liverpool with salt for St Peter’s. He had lived sufficiently long at the last place to know that nothing but small fishing schooners could pass over the bar; yet he quite overlooked this in his calculation in loading his ship, until he arrived abreast the harbour, where, fortunately, fine weather favoured him so far as to admit anchoring on the outside for a few days. The ship was then sent to seek for a deeper harbour to unload her cargo – I believe to Gaspé or Quebec.

[299]

an immense barn, a very superior grist-mill, offices, &c., on the lands occupied by themselves. The lands round the bay and rivers have, however, been most wretchedly managed, although this part of the country was in a very flourishing condition, and well cultivated, when possessed by the French.

Greenwich, situated on the peninsula, between St Peter’s Bay and the Gulf of St Lawrence, is a charming spot, with extensively cleared lands, once well cultivated. This estate is involved in a Chancery suit, not yet, I believe, decided; and the son of the original complainant died old and grey, five years ago, completely worn out in the cause. It justly belongs to Mr Cambridge of Bristol.

District of the Capes. – This district extends along the north shore of the island, from St Peter’s to the east point. There are no harbours between these two places; but several ponds, or small lakes, intervene. For a considerable distance back from the gulf shore, the lands are entirely cleared, with the exception of detached spots or clumps of the spruce fir. The inhabitants are principally from the west of Scotland, and from the Hebrides, and their labour has been chiefly applied to agriculture. They raise, even with the old mode of husbandry, to which they tenaciously adhere, valuable crops; and the greater part of the wheat, barley, oats, and pork brought to Charlotte Town, is from this district. It has the advantage of having a regular supply of seaware (various marine weeds) thrown on its shore, which makes excellent manure, particularly for barley.

[300]

Colville, Rollo, Fortune, and Boughton Bays, are small harbours, with thriving settlements, situated on the south-east of the island, between Three Rivers and the east point. The inhabitants are principally Highlanders and Acadian French.

Murray Harbour lies between Cape Bear and Three Rivers. It is well sheltered; but the entrance is intricate, and large ships can only take in part of their cargoes within the bar. Several cargoes of timber have been exported from this place, and a number of excellent ships, brigs, and small vessels, have been built here by Messrs Cambridge and Sons, whose extensive establishments, mills, ship-yards, &c., have for many years afforded employment to a number of people. The cultivation of the soil has, however, for a long time been neglected; but an accession of industrious people, who have settled her within the last few years, are making great improvements.

The lands in the townships abutting and adjoining Murray Harbour, are very fertile, and form an extensive district, extending from Three Rivers to the Earl of Selkirk’s property, at Wood Island. There are some fine and beautiful farms fronting on the shores, and some small lagoons, particularly at Gaspereau pond, situated to the eastward of Murray Harbour.

Belfast. – This district may be said to include the villages of Great and Little Belfast, Orwell, and Point Prime, with the settlements at Pinnette River, Flat River, Belle Creek, and Wood Islands. At

[301]

the time the island was taken from the French, a few inhabitants were settled in this district; but from that period, the lands, in a great measure, remained unoccupied until the year 1803, when the late enterprising Earl of Selkirk arrived on the island with 800 emigrants, whom he settled along the fronts of the townships that now contain those flourishing settlements. His lordship brought his colony from the Highlands and Isles of Scotland, and by the convenience of the tenures under which he gave them lands, and by persevering industry on their part, these people have arrived at more comfort and happiness than they experienced before. The soil in this district is excellent; the population has increased in number, with the accession of friends and relatives chiefly, and the natural increase of the first colonists, to nearly 4000. They raise heavy crops, the overplus of which they carry either to Charlotte Town, Pictou, Halifax, or Newfoundland.

His lordship observes, in his able work on emigration – "I had undertaken to settle these lands with emigrants whose views were directed towards the United States; and, without any wish to increase the general spirit of emigration, I could not avoid giving more than ordinary advantages to those who should join me. *** To induce people to embark in the undertaking, was, however, the least part of my task. The difficulties which a new settler has to struggle with, are so great and various, that in the oldest and best-established colonies they are not to be avoided altogether. *** Of these discou-

[302]

ragements the emigrant is seldom fully aware. He has a new set of ideas to acquire; the knowledge which his previous experience has accumulated can seldom be applied; his ignorance as to the circumstances of the country meet him on every occasion. *** The combined effect of these accumulated difficulties is seen in the long infancy of most new-settled countries. *** I will not assert that the people I took there [to Prince Edward Island] have totally escaped all difficulties and discouragements, but the arrangements for their accommodation have had so much success, that few, perhaps, in their situation, have suffered less, or have seen their difficulties so soon at an end. *** These people, amounting to about eight hundred persons, of all ages, reached the island in their ships, on the 7th, 9th, and 27th August, 1803. It had been my intention to come to the island some time before any of the settlers, in order that every requisite preparation might be made. In this, however, a number of untoward circumstances occurred to disappoint me; and on arriving at the capital of the island, I learned that the ship of most importance had just arrived, and the passengers were landing at a place previously appointed for the purpose. *** I lost no time in proceeding to the spot, where I found that the people had already lodged themselves in temporary wigwams (tents composed of poles and branches).

"The settlers had spread themselves along the shore for the distance of about half a mile, upon the site of an old French village, which had been de-

[303]

stroyed and abandoned after the capture of the island by the British forces in 1758. The land, which had formerly been overgrown with wood, was overgrown again with thickets of young trees, interspersed with grassy glades. *** I arrived at the place late in the evening, and it had then a very striking appearance. Each family had kindled a large fire near their wigwams, and round these were assembled groups of figures, whose peculiar national dress added to the singularity of the surrounding scene; confused heaps of baggage were everywhere piled together beside their wild habitations; and by the number of fires, the whole woods were illumined. At the end of the line of encampment I pitched my tent, and was surrounded in the morning by a numerous assemblage of people, whose behaviour indicated that they looked to nothing less than a restoration of the happy days of clanship. *** These hardy people thought little of the inconvenience they felt from the slightness of the shelter they put up for themselves."

His lordship then states numerous difficulties attending the location of the emigrants, and then proceeds: - "I could not but regret the time which had been lost; but I had satisfaction in reflecting that the settlers had begun the culture of their farms, with their little capitals unimpaired. *** I quitted the island in September 1803, and after an extensive tour on the continent of America, returned at the end of the same month in the following year. It was with the utmost satisfaction I then found that my plans had been followed up with attention and judg-

[304]

ment. *** I found the settlers engaged in securing the harvest which their industry had produced. There were three or four families who had not gathered a crop adequate to their own supply; but many others had a considerable superabundance."

I had, while in America, frequent opportunities of knowing the condition of these colonists; and, if possessing land, good houses, large stocks of cattle, abundance of provisions, and a large overplus of produce to sell for articles of convenience, together with being free of debt, be considered to constitute independent circumstances, they are certainly in that state.

Tryon is situated about twenty miles west of Charlotte Town, nearly opposite to Bay de Verts, in Nova Scotia. It is one of the most populous, and considered the prettiest village on the island. A serpentine river winds through it; on each side of which are beautiful farms. The tide flows up about two miles; but the harbour will only admit of small schooners and boats, it having a dangerous bar at the entrance: extensive clearings were made here when possessed by the French.

Bedeque is situated on the south-west part of the island, about eighteen miles from Tryon. It is populously settled on the different sides of the two rivers into which the harbour branches. The harbour is well sheltered by a small island, near which ships anchor and load. There are two or three ship-building establishments here; and it has for some time been a shipping port for timber.

Egmont Bay lies to the west of Bedeque. It is

[305]

a large open bay, sixteen miles broad from the west point to Cape Egmont, and about ten deep. Perceval, Enmore, and two other small rivers, fall into it; on the borders of which are excellent marshes. There is no harbour within this bay for large vessels; and as the shoals lie a considerable distance off, it is dangerous for strangers to venture in, even with small vessels. The inhabitants are chiefly Acadian French, who live in three small thriving villages, on the east side of the bay. The whole population consists only of thirty-nine families.*

*Coming down the Gulf of St. Lawrence, from the Bay de Chaleur, in 1819, in a large whale boat, we were driven into this bay, but could not approach within a quarter of a mile of the shore, in consequence of its being there lined by a succession of narrow sand bars, with channels about four feet deep between them. An Acadian, nearly one hundred years old, came out to us on horseback, and carried us, one at a time, behind him on the horse to the shore. We met with great hospitality among the simple Acadians. I stopped in the old patriarch’s house; and the bed in which the priest, who visited the village twice a-year, slept, was allotted to me.

There were none except the venerable Acadian and his wife living in the house. He laboured daily in the fields; and she not only frequently assisted him, but cooked, washed, and made and mended his clothes. He gave me much information about the early condition of the island, as he was born on it, and was present when it surrendered to the English, in 1758. Talking of himself, he said, "I am the father of every family" (twenty-four at that time) "in the village; for there is not one of those houses in which I have not either a son, daughter, grandson, or grand-daughter married; and I have also several great-grand-children. Look at my old wife and me," said he, "now living alone as we were when first married. We need not work, it is true, for our children would willingly provide us plenty, even if we had not money laid by. But we know, that if we did not work, we would soon die. Besides, we are in good health and strong, and therefore it would be a great sin to be idle. Neither of us were scarcely ever sick. I never had a headach; and I never took physic in my life." This man and his wife are, I believe, both still living.

[306]

Hillsborough river enters the country in a north-easterly direction. The tide flows twenty miles farther up than Charlotte Town; and three small rivers branch off to the south.

The scenery at and near the head of this river, is rich and pretty. Mount Stewart, the property and present residence of John Stewart, Esq., late paymaster to the troops of Newfoundland, and Speaker of the present House of Assembly, is a most charming spot; and the prospect from the house, which stands on a rising ground, about half a mile from the river, is truly beautiful. Downwards, the view commands several windings of the Hillsborough, and part of Pisquit river: the edges of each are fringed with marsh grass, and fertile farms range along the banks, while trees of majestic birch, beech, and maple, grow luxuriantly on the south side, and spruce-fir, larch, beech, and poplar on the north, fill up the background. Upwards, the meandering river, on which one may now and then see passengers crossing in a log canoe, or an Indian, with his family, paddling along in a bark one, together with a view of the large Catholic chapel at St Andrew’s, the seat of the Catholic bishop,* and the surrounding farms and woods, form another agreeable landscape.

*The Right Reverend Aneas McEacharen, titular Bishop of Rouen, and excellent and venerable character, equally esteemed by the members of every religious profession in the colony.

[307]

York river penetrates the island in a north-westerly course, the tide flowing about nine miles up. On each side there is a straggling settlement; and many of the inhabitants have excellent farms, with a considerable portion of the land under cultivation.

Elliot river branches off nearly west from Charlotte Town harbour, the tide flowing about twelve miles up. A number of small streams fall into this river; and the lands on both sides exhibit beautiful farms, with rather a thickly-settled population. The scenery about this river has as much of the romantic character as is to be met with in any part of the island.

There are a number of other, though lesser settlements. The principal of these are – Tigniche, near the North Cape, the inhabitants of which are Acadian French; Crapaud and De Sable, both thriving fast, between Hillsborough Bay and Tryon; Cape Traverse and Seven Mile Bay, between Tryon and Bedeque; and the Acadian settlement at Cape Egmont. Settlements are also forming along the roads, particularly in the vicinity of Charlotte Town. The only tract of extent, bordering on the coast, without settlers, is that lying between the North Cape and the West Point. There are several fine streams and ponds in this district; and the soil is rich, and covered with lofty trees. Its only disadvantage is, having no harbour; but it is always safe to land in a boat, if the wind does not blow strongly on the shore. Fish of various kinds swarm along the coast.

[308]

CHAPTER II.

Climate – Soil – Natural Productions – Wild Animals, &c..

The climate of Prince Edward Island, owing to its lying within the Gulf of St Lawrence, partakes, in some measure, of the climate of the neighbouring countries; but the difference is greater than any one who has not lived in the colony would imagine.

In Lower Canada, the winter is nearly two months longer, the frosts more severe, and the snows deeper; while the temperature, during summer, is equally hot. In Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Cape Breton, the frosts are equally severe, the transitions from one extreme of temperature to another more sudden, and fogs frequent along those parts that border on the Atlantic and Bay of Fundy.

The atmosphere of this island is noted for being free of fogs. A day foggy throughout seldom occurs during a year; and in general not more than four or five that are partially so. A misty fog appears sometimes on a summer or autumnal morning, occasioned by the exhalation of the dew that falls during the night, but which the rising sun quickly dissipates.

The absence of fogs in this colony has been vari-

[309]

ously accounted for, but never yet from what I conceive the true cause; and which I consider to be, in the first place, that the waters which wash the shores of the island do not come in immediate contact with those of a different temperature; and, secondly, that Cape Breton and Newfoundland, both of which are high and mountainous, lie between it and the Atlantic. These islands arrest the fogs, which would otherwise be driven by strong easterly winds from the banks to Prince Edward Island. Fogs are, it is true, occasionally met with at the entrance of river St Lawrence; but these are produced by known natural causes. A strong current of cold water runs from the Atlantic through the strait of Belle Isle; its principal stream passes between the island of Anticosti and the coast of Labrador, and coming in contact with the warmer stream of the St Lawrence, a fog is produced.

Prince Edward Island lies so far within the deep bay, formed between Cape Rosier and the north cape of Cape Breton, that the waters which surround it do not mix within many miles of its shores with those of the Atlantic.

As regards the salubrity of the island, it is agreed by all who have lived any time on it, and have compared its climate with that of other countries, that there are few places where health is enjoyed with less interruption. What Mr Stewart, in his excellent account, at the time it was written, of Prince Edward Island, says of the climate, is, I think, strictly true:

[310]

"The fevers and other diseases of the United States are unknown here; no person ever saw an intermittent fever produced on the island, nor will that complaint, when brought here, ever stand above a few days against the influence of the climate. I have seen thirty Hessian soldiers, who brought this disease from the southward, and who were so much reduced thereby as to be carried on shore in blankets, all recover in a very short time; few of them had any return or fit of the complaint after the first forty-eight hours from their landing on the island."

Pulmonary consumption, which is so common and so very destructive in the northern and central states of America, is not often met with here. Probably ten cases of this complaint have not occurred since the settlement of the colony. Colds and rheumatisms are the most common complaints: the first generally affect the head more than the breast, and the last seldom prove mortal. A very large proportion of the people live to old age, and then die of no acute disease, but by the gradual decay of nature.

"Deaths between twenty and fifty years of age are but few, when compared with those of most other countries; and I trust I do not exaggerate the fact, when I state, that not one person in fifty (all accidents included) dies in a year. It follows, from what has been said, that mankind must increase very fast in such a climate; accordingly, large families are almost universal. Industry always secures a comfortable subsistence, which encourages early marriages:

[311]

the women are often grandmothers at forty; and the mother and daughter may each be seen with a child at the breast at the same time"*

The diseases at present commonly known, are usually the consequence of colds or intemperance, if we except consumptions, which I have observed in most cases to be constitutional; and the young women born on the island appear to be more subject to this malady than those who remove to the colony from Europe. The climate is decidedly salubrious. Bilious complaints are unknown; and I have conversed with several people who were affected with ill health previous to their settling in this colony, who afterwards enjoyed all the comforts of an unimpaired constitution.

The absence of damp weather and noxious exhalations, those certain generators of disease; and the island having no lakes, or few ponds of fresh water, while it is at the same time surrounded by the sea, will account satisfactorily for the excellence of its climate.

The general structure of the soil is, first a thin layer of black or brown mould, composed of decayed vegetable substances; then, to the depth of a foot, or more, a light loam prevails, inclining in some places to a sandy, in others to a clayey character; below which, a stiff clay, resting on sandstone, predominates. The prevailing colour of both soil and stone is red.

*Account of Prince Edward Island, by John Stewart, Esq., late paymaster to the forces at Newfoundland. London, 1806.

[312]

To this general character of the soil there are but few exceptions: these are the bogs, or swamps, which consist either of a soft spongy turf, or a deep layer of wet black mould, resting on white clay, or sand.

In its natural state, the quality of the soil may be readily ascertained by the description of wood growing on it; it being richest where the maple, beech, black birch, and a mixture of other trees, grow, and less fertile where the pine, spruce, larch, and other varieties of the fir tribe, are most numerous.

The soil is fertile; and there is scarcely a stone on the surface of the island that will impede the progress of the plough. There is no limestone nor gypsum, nor has coal yet been discovered, although indications of its existence are produced. Iron ore is by many thought to abound, but no specimens have as yet been discovered, although the soil is in different places impregnated with oxide of iron; and a sediment is lodged in the rivulets running from various springs, consisting of metallic oxides.

Red clay, of superior quality for bricks, abounds in all parts of the island; and a strong white clay, fit for potters’ use, is met with, but not in great quantities. A solitary block of granite presents itself occasionally to the traveler; but two stones of this description are seldom found within a mile of each other.

Volney and some other writers have remarked, that the granite base of the Alleghany mountains extends so far as to form the rocky stratum of all the countries of America lying to the eastward of them. To this, as a general rule, there is more than one

[313]

exception. The base of Prince Edward Island, which is sandstone, appears to extend under the bed of Northumberland Strait, into the northern part of Nova Scotia, and into the eastern division of New Brunswick, until it is lost in its line of contact with the granite base of the Alleghanies, about the river Nipisighit.

On some of the bogs, or swamps, of this island, there is scarcely any thing but shrubs and moss growing; these are rather dry, and resemble the turf bogs in Ireland. Others again are wet, spongy, and deep, producing dwarf species of alder, long grass, and a variety of shrubs. Cattle are frequently, in the spring of the year, lost in these swamps. Such portions of these lands as have been drained, form excellent meadows.

There are other tracts called barrens, some of which, in a natural state, produce nothing but dry moss, or a few shrubs. The soil of these spots is a light brown, or whitish sand. Some of the lands formerly covered with pine forests, now incline to this character. Both swamps and barrens, however, bear but a small proportion to the whole surface of the island; and as they all may, with judicious management, be improved advantageously, it cannot be said that there is an acre of the whole incapable of cultivation. The marshes, which are overflowed by the tide, rear a strong nutritious grass, and, when dyked, yield heavy crops of wheat or hay.

Large tracts of the original pine forests have been destroyed by fires, which have raged over the island at

[314]

different periods. In these places white birches, spruce-firs, poplars, and wild cherry-trees, have sprung up. The largest trees of this second growth that I have seen, were from twelve to fifteen inches diameter, and growing in places laid waste by a tremendous fire, which raged in 1750. At its first settlement, and previous to the destruction, by fire, at different periods, of much valuable timber, the island was altogether covered with wood, and contained forests of majestic pines. Trees of this genus still abound, but not in extensive groves; and from the quantity which has been exported to England, there is not more pine at present growing on the island than will be required by the inhabitants for house and ship-building, and other purposes. The principal kinds of other trees are spruce-fir, hemlock, beech, birch, and maple, growing in abundance; oak, elm, ash, and larch, are not plentiful, and the quality of the first very inferior.

Poplars, of great dimensions, are plentiful; white cedar is found growing in the northern parts. Many other kinds of trees are met with, such as dogwood, alder, wild cherry-tree, Indian pear-tree, &c., and most of the shrubs, wild fruits, herbs, and grasses, common to other parts of British North America. Sarsaparilla, ginseng, and probably many other medicinal plants, are plentiful in all parts of the island. Among the wild fruits, raspberries, strawberries, cranberries, which are very large, blueberries, and whortleberries, are astonishingly abundant.

The principal native quadrupeds are, bears, loup-

[315]

cerviers [Canada Lynx], foxes, hares, otters, musquashes [Muskrat], minks, squirrels, weasels, &c.

For many years after the settlement of the colony, bears were very numerous, and exceedingly annoying and injurious to the inhabitants, destroying their black cattle, sheep, and hogs. They are now much reduced in number, and rarely met with. A premium for their destruction, as well as that of the loup-cervier, is granted by the colonial government.

The loup-cervier still commits great ravages among the sheep; and one will kill several of those innocent creatures during the night, as it sucks the blood only, leaving the flesh untouched.

Foxes and hares are numerous. Otters, martins, and musk-rats, being so long hunted on account of their skins, have become scarce. The flying, brown, and striped varieties of squirrels, are plentiful. Weasels and ermines are native animals, but very rarely seen.

Formerly, mice were in some seasons so very numerous, as to destroy the greater part of the corn about a week before it ripened. Within the last twenty years, little injury has been done by these mischievous animals, although they have been known in such swarms, previous to that period, as to cut down whole fields of wheat in one night.

For many years after the settlement of the colony, walruses, or sea-cows, frequented different parts along the shores, and the numbers killed were not only considerable, but they afforded a source of advantageous enterprise to the inhabitants. Their teeth,

[316]

from fifteen inches to two feet in length, were considered as fine a quality of ivory as those of the elephant; and their skins, about an inch in thickness, were cut into stripes for traces, and used on the island, or exported to Quebec. They afforded also excellent oil. None of these animals have appeared near the shores of the island for thirty years, but are still seen occasionally at the Magdalene Islands, and other places to the northward.

Seals of the description called harbour seal, appear in the bays, and round the shores, during the summer and autumn; and in the spring, immense numbers sometimes come down on the ice from the northward. These are the same kind as the ice seals of Newfoundland.

Most of the birds described in a former chapter frequent this island; and owls, crows, ravens, woodpeckers, partridges, with some others, remain during the whole year.

Partridges are larger, and considered finer, than in England. A provincial law prohibits the shooting of them between the first of April and the first of September. Wild pigeons arrive in great flocks in summer from the southward, and breed in the woods.

Wild geese appear in March, and, after remaining five or six weeks, proceed to the northward to breed, from whence they return in September, and leave for the southward in November. Brent geese and wild ducks are plentiful.

There are no game laws, unless the provincial act for preserving partridges during four months be

[317]

considered such; nor does it appear that persons can be hindered from shooting, even on lands under cultivation, unless by proceeding against them as trespassers.

The only reptiles known on the island are brown and striped snakes, neither of which are venomous, and the red viper, toad, bull-frog, and green-frog. There are several beautiful varieties of the butterfly, which, with locusts, grasshoppers, crickets, horned-beetle, bug-adder, black fly, adder fly, horse fly, sand fly, mosquito, ant, horned wasp, humble fee, fire fly, and a numerous variety of spiders, are the principal insects.

Mosquitoes and sand flies are only annoying during the heat of summer, in the neighbourhood of marshes, and in the woods; where the lands are cleared to any extent, they are seldom troublesome.

The varieties of fishes that swarm in the harbours and rivers, or around the shores, and that abound on the different fishing banks in the vicinage of the island, are numerous, each abounding in great plenty, and of the same kind and quality as those already described.

The varieties of shell-fish are oysters, clams, mussels, razor shell-fish, wilks, lobsters, crabs, shrimps, &c.

The oysters are considered the finest in America, and equally delicious as those taken on the English shores. There are two or three varieties, the largest of which is from six to fifteen inches long. There were so many cargoes taken away annually to Que-

[318]

bec and Halifax, that the legislative assembly passed an act, four years ago, prohibiting their export for some time.

Lobsters are very plentiful, and, when in season, excellent.

The kinds of fish usually brought to Charlotte Town market, with which, however, it is but badly supplied, are cod, haddock, mackerel, herring, salmon, trout, eels, perch, smelts, &c. No market can be more easily or regularly supplied with fish than that of Charlotte Town; yet, from indolence, and the ease with which the labouring classes can procure food from the soil, it is the worst fish-market in the world.

[319]

CHAPTER III.

Agricultural Productions – Seed time – Harvest – Horned Cattle – Sheep –

Swine – Horses – Scotch Highlanders slovenly Farmers – Manner of Clear-

Ing and Cultivating Forest Lands – Consequence of Fires in the Woods –

Manures – Agricultural Society – Habitations of New Settlers, &c.The excellence of its soil, its climate, and the configuration of its surface, adapt the lands of Prince Edward Island more particularly for agriculture than for any other purpose.

All kinds of grain and vegetables raised in England, ripen in perfection. Wheat is raised in abundance for the consumption of the inhabitants, and a surplus is exported to Nova Scotia. Both summer and winter rye, and buckwheat, produce weighty crops; but the culture of these grains is scarcely attended to. Barley and oats thrive well, and are, in weight and quality, equal to any met with in the English markets, and superior to what are produced in the United States.

Beans of all kinds yield plentiful returns. Peas, when not injured by worms, which is often the case, thrive well; and turnips are sometimes liable to injury from flies and worms. In no country do parsnips, carrots, beets, mangel-wurzel, or potatoes, yield

[320]

more bountiful crops. Cucumbers, salads, cabbages, cauliflowers, asparagus, and indeed all culinary vegetables common in England, arrive at perfection. Cherries, plums, damsons, black, red, and white currants, ripen perfectly, and are large and delicious. Gooseberries do not always succeed, but probably from improper management.

The apples raised are inferior in quality, but certainly from want of attention, as many of the trees planted by the French, previous to the conquest of the island in 1758, are still bearing fruit; and some fine samples of apples are produced by those farmers who have taken pains in rearing the trees.

Indian corn, or maize, is occasionally planted, but it does not by any means thrive so well as in New Brunswick or Nova Scotia, nor do I consider it so congenial to the soil.

Flax is raised, of excellent quality, and manufactured by the farmers’ wives into linen for domestic use. This article might be cultivated extensively for exportation.

Hemp will grow, but not to the same perfection as in Upper Canada, or some parts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

The principal grasses are timothy, red and white clover, and a kind of soft indigenous upland grass, of which sheep are very fond; also marsh grasses, on which young and dry cattle are fed during the winter months.

As a few cold days and wet weather frequently occur in the latter end of April, or the first week

[321]

of May, wheat or oats are seldom sown until the first of the latter month. Barley will ripen if sown before the 20th of June, although it is generally sown earlier. Potatoes are planted about the last of May, or before the middle of June, and often later. Turnip seed is sown about the middle of July; some prefer sowing it the first week in August, in which case the leaves are not so liable to injury from worms. Gardening commences early in May, and generally combines the different departments of fruits, flowers, and vegetables.

Haymaking begins in the latter end of July, and as the weather is commonly very dry at this time, it is attended with little trouble in curing. Hay is sometimes put away under cover, but oftener made into stacks or ricks. Experienced farmers say, that the common run of old settlers on the island dry their hay before they stack it. Barley is reaped in August; there are two varieties of it, five-rowed and two-rowed ears. The wheat and oat harvest commences sometimes before, but generally after the first of September. Some use a cradle for cutting their grain, and afterwards make it up into sheaves and stooks, but the common way is to reap and lay it up in sheaves, and then gather and stack it in the same manner as in England.

Potatoes and turnips are left undug until the middle or end of October: the first are generally ploughed up, except on new land, where the hoe alone is used. Parsnips may remain in the ground during winter,

[322]

and are finer when dug up in spring than at any other period.

Milch cows, and such horses and cattle as require most care, are housed in November; but December is the usual month for housing cattle regularly. Sheep thrive better by being left out all winter; but they require to be fed, and it is necessary to have a shelter without a roof, to guard against the cold winds and snow drift.

Black cattle are generally smaller than in England: a good ox will weigh from eight to nine hundred pounds, but the common run will not exceed six or seven hundred. The beef is usually very fine and tender.

Sheep thrive remarkably well; but, until lately, very little care was observed in improving the breed. The late Attorney-General, Mr Johnston, kept a flock of fine sheep, equal to any in England, on his excellently cultivated farm near Charlotte Town; and since that time, other farmers are following his example, from observing that the quantity of wool they produced was more than double the weight yielded by the common breed. The mutton, however, of the old breed, is usually fat and well-flavoured.

Swine seem to thrive here as well as in any country, and the pork brought to Charlotte Town by the farmers, is probably equal in general to that met with in the Irish market; but from want of proper care in rearing, and possessing a good breed of pigs, one half the number raised on the island are tall, long-snouted animals, resembling greyhounds nearly

[323]

as much as they do the better kind of hogs; and when, as they generally are, left during summer to range uncontrolled through the woods, they are as wild and swift as foxes.

The horses are, with few exceptions, small, and capable of performing long journeys, and enduring great fatigue, with much spirit. During summer, it is usual to take them off the grass, and ride them the same day thirty or forty miles without feeding, frequently on bad roads, then turn them loose to feed on grass during the night, and ride them back on the following day: all this is performed frequently without apparent injury to the animal. The old Canadian breed, originally from Normandy, are the hardiest horses, and seem as if formed for the severe usage they undergo. Their owners take them almost every week during winter to Charlotte Town, twenty or thirty miles, and leave them tied, often without food, to a post or fence for several hours, and return home with them the same night; the horse hungry and sober, but the master rarely in the latter state. I have been told by an old Acadian Frenchman, that for several years after the conquest of the island, a vast number of horses were running in a wild state about the eastern parts. Such horses as are taken good care of, and have been trained, make very agreeable saddle, or carriage horses. The breed is likely now to improve fast, from those introduced by Colonel Ready, the present governor; and this may be said of horned cattle, sheep, and hogs; for, when last on the island in 1828, I was astonished at the

[324]

improvement in the horses, cattle, hogs, and sheep exhibited at the agricultural show, and also at the excellence of the wheat, oats, and other produce.

The greater number of farmers, particularly the Highland Scotch, keep by far too many cattle for the quantity of provender they usually have to feed them with during winter. These people think if they can manage to carry their cattle through the winter, they are doing well; but the consequence is, that their cattle, especially milch cows, are in such lean condition in spring, that they are not in tolerable order until July. Until milch cows also are prevented from ranging at large, as almost all the cattle are allowed to do, and until they are better fed during winter, one half the quantity of butter and cheese that might be expected, will not be made on the island. Those who keep their cows within enclosures are sensible of this. The prejudices of the old settlers, however, as regards this, and other customs and habits, must necessarily give way to the force of example set before them by the superior management of many farmers who follow the most approved modes of husbandry and grazing.

Much may also be expected from the exertions of agricultural societies, established since Governor Ready’s appointment to the administration. Cattle shows, and exhibitions of agricultural produce, are established. Prizes are given to those who produce the best specimens of each. It is also pleasing to observe the improvement in the mode of cultivating the lands, which has spread over the colony during

[325]

the last few years, and which may be attributed principally to the force of example, set by a few of the old settlers, chiefly the loyalists and Lowland Scotch, and by an acquisition of industrious and frugal settlers from Yorkshire, in England, and from Dumfries-shire and Perthshire, in Scotland.

The principal disadvantage connected with this island, and in fact the only one of any importance, is the length of the winters, which renders it necessary to have a large store of hay for supporting live stock; and which also, from the abrupt opening of spring and summer, abridges the season for sowing and planting. These disadvantages are, however, felt with equal severity in Prussia, and over a great part of Germany, where the people employed in agricultural pursuits form the majority of the inhabitants.

About a ton of hay, with straw for each, taking large and small together, is requisite to winter black cattle properly. The winter season has also many advantages – wood and firing poles are easily brought from the forests, over the smooth slippery roads made by the frosts and snows, and distances are shortened by the bays and rivers being frozen over. The ground is also considered to be fertilized by deep snows and frosts; and there are few farmers who consider the winter and impediment to agriculture, otherwise than the spring opening so suddenly upon them, and the astonishing quickness of vegetation, leaving them only five or six weeks for preparing the soil, and sowing and planting. When we consider, however, that the autumn and fall are

[326]

much finer, and of longer duration than in Europe, and the winter setting in generally much later, the farmers have, in reality, little cause to complain of the seasons, as they have abundant time to plough all the grounds in the fall, which is, at the same time, known to be the most proper season for American tillage.

The common plan of laying out farms in this colony, is in lots containing one hundred acres each, having a front of ten chains, either on the sea-shore, a bay, river, or road, and running one hundred chains back. This plan, from the farms being in strips instead of square blocks, is often objected to; but it has many advantages, by giving a greater number of settlers the benefits of roads, shores, and running streams.

It is curious and interesting to observe the progress which a new settler makes in clearing and cultivating a wood farm, from the period he commences in the forest, until he has reclaimed a sufficient quantity of land to enable him to follow the mode of cultivation he practiced in his native country. As the same course is, with little variation, followed by all new settlers in every part of America, the following description may, to avoid repetition, be considered applicable to all of British American settlement: -

The first object is to select the farm among such vacant lands as are most desirable, and after obtaining the necessary tenure, the settler commences, usually assisted in his first operations by the nearest

[327]

inhabitants, by cutting down the trees on the site of his intended habitation, and those growing on the ground immediately adjoining. This operation is performed with the axe, by cutting a notch on each side of the tree, about two feet above the ground, and rather more than half through on the side it is intended the tree should fall on. The lower edges of these notches are cut horizontally, the upper making an angle of about 60° with the ground. The trees are all felled in the same direction, and after lopping off the principal branches, cut into ten or twelve feet lengths. On the spot on which the house is to be erected, these junks are rolled away, and the smaller parts cleared off, or burnt.

The habitations which the new settlers first erect, are all nearly in the same style, and in imitation of, or altogether like, the dwellings of an American backwoodsman, constructed in the rudest manner. Round logs, from fifteen to twenty feet long, without the least dressing, are laid horizontally over each other, and notched in at the corners to allow them to come, along the walls, within about an inch of each other. One is first laid on each side to begin the walls, then one at each end, and the building is raised in this manner, by a succession of logs crossing and binding each other at the corners, until the wall is six or seven feet high. The seams are closed with moss or clay; three or four rafters are then raised to support the roof, which is covered with boards, or more frequently with the rinds of birch or fir-trees, and thatched with spruce branches, or, if near the sea-

[328]

coast, with a long marine grass, which is found in quantities along the shores. Poles are laid over this thatch, tied together with birch withes, to keep the whole securely down. A wooden frame-work, placed on a slight foundation of stone roughly raised a few feet above the ground, leads through the roof, which, with its sides closed up with clay and straw kneaded together, forms the chimney, A space large enough for a door, and another for a window, is cut through the walls; and in the centre of the cottage, a square pit or cellar is dug, for the purpose of preserving potatoes or other vegetables during the winter; over this pit, a floor of boards, or logs hewed flat on the upper side, is laid, and another over head, to form a sort of garret. When the door is hung, a window sash, with six or nine, or sometimes twelve panes of glass, is fixed, and one, two, or three truckle beds are put up: the habitation is then considered ready to receive the new settler and his family. Although such a dwelling has certainly nothing handsome, comfortable, or even attractive, unless it by its rudeness in appearance, yet it is by no means so miserable a lodging as the habitations of the poorer peasantry in Ireland, and in some parts of England and Scotland. In a few years, however, a much better house is built, with two or more rooms, by all steady industrious settlers.*

*The manner of building these habitations, and the mode of clearing and cultivating forest lands, may be considered equally applicable to all the other colonies.

[329]

Previous to commencing the cultivation of wood lands, the trees that are cut down, lopped, and cut into lengths, are, when the proper season arrives, generally in May, set on fire, which consumes all the branches and small wood. The logs are then either piled in heaps and burnt, or rolled away for fencing. Those who can afford the expense, use oxen to haul off the large unconsumed timber. The surface of the ground, the remaining wood, is all black and charred; working on it, and preparing it for the seed, is as disagreeable probably as any labour in which a man can be engaged. Men, women, and children, however, must employ themselves in gathering and burning the rubbish, and in such parts of labour as the strength of each adapts them to. If the ground be intended for grain, it is sown, without tillage, over the surface, and the seed covered with a hoe. By some a triangular harrow is used, in place of the hoe, to shorten labour. Others break up the earth with a one-handled plough, (the old Dutch plough,) which has the share and coulter locked into each other, drawn also by oxen, while a man attends with an axe, to cut the roots in its way. Little regard is paid in this case, to making straight furrows, the object being no more than to work up the ground. With such rude preparation, however, three successive good crops are raised without any manure. Potatoes are planted in round hollows, scooped four or five inches deep, and about twenty in circumference, in which three or five sets are planted, and covered over with a hoe. Indian corn, cucumbers, pumpkins, pease, and

[330]

beans, are cultivated on new lands, in the same manner as potatoes. Grain of all kinds, turnip, hemp, flax, and grass seed, are sown over the surface, and covered by means of a hoe, rake, or harrow. Wheat is usually sown on the same ground, the year after potatoes, without ploughing, but covering the seed with a rake or harrow; and oats are sown on the same land the following year. Some farmers, and it is certainly a prudent plan, sow timothy, or clover seed, the second year, along with the wheat, and afterwards let the ground remain under grass until the stumps of the trees can be easily got out, which usually requires three or four years. With a little additional labour, these obstructions to cultivation might be removed the second year. The roots of spruce, birch, and beech decay soonest; those of pine and hemlock scarcely decay in an age. After the stumps are removed from the soil, and those natural hillocks, called cradle hills,* which render the whole of the forests of America full of inequalities of from one to three feet high, are leveled, the plough may always be used, and the system of husbandry followed that is most approved of in England or Scotland.

When the soil is exhausted by copping, which, on alluvial lands, is scarcely ever the case, various manures may be procured and applied. In many parts of America, limestone, gypsum, &c. are abundant; but little else except stable dung is ever used.

*These tumuli have been formed during the growth of the forest trees, by the extension of their large roots, and the portion of the trunks under the ground, swelling the earth gradually into hillocks.

[331]

Composts are rarely known; and different manures, that would fertilize the soil, are so much disregarded, that, generally speaking, the cultivation of the soil is conducted in so slovenly a manner, that it appears astonishing how many of the settlers raise enough to support their families. In this island, within many of the bays and rivers, numerous banks of mussel-mud abound, which consists of mussels, shells, and mud composed of decayed vegetable and other substances. This forms an extremely rich manure, containing about forty-five parts of the carbonate of lime, and imparts extraordinary fertility for ten or twelve years to the soil. Sea-weed, or ware, which is thrown on the shores, especially on the north side of the island, in great quantities, is another excellent manure, particularly for barely crops; and even the common mud, which abounds in the creeks, may be applied as a manure with advantage.

[332]

CHAPTER IV.

Trade, &c.

When this island was possessed by the French, the population being unimportant, little trade was carried on by the inhabitants; and the government, aware that its superior natural advantages would drain off most of the settlers at and near Louisburg, discouraged its fisheries, by not allowing them to be carried on except in one or two harbours. The inhabitants were, in consequence, confined to agriculture.

On the colony being settled by the British, a trade, of no great extent, however, was carried on in the articles of fish, oil, sea-cow skins, and seal-skins, which were exported to Quebec, Halifax, and Boston. The people then engaged in the fisheries were principally Acadian French, who built them small shallops and boats on the island.

As the best fishing banks within the Gulf of St. Lawrence lie in the immediate vicinage of this island, it seems, at first, rather surprising that extensive fisheries have not before this time been established. There have been, it is true, some attempts of the kind made, which, from different causes, have failed. The American revolutionary war affected the first

[333]

trials, and the others fell through from mismanagement, want of capital, and circumstances peculiar to the natural state of the colony. The last cause might naturally be considered as a decided advantage over Newfoundland, for carrying on the fisheries, when we discover that it arises from the island producing great plenty of all kinds of provisions for fisheries, abundance of wood for building vessels and boats, and numerous safe and convenient harbours. The fact is, that the prime necessaries of life being procured with such ease from the soil, and small vessels being so readily built, for carrying overplus produce from the different harbours to where it is wanted, and for which various articles of luxury are obtained, form the great obstacle at present to the success of fishing establishments. This objection will also continue until the country becomes so populous that a livelihood can be obtained from the sea, with much the same labour, or price of labour, as from the soil; for at present it is out of the question for a merchant who would supply people for fishing voyages, to depend on the industry of those whom he employed or trusted, as is the case in Newfoundland, where the fisheries have so long formed the primary occupation of the inhabitants.

The timber trade has been for many years of some importance, by employing a number of ships and men; but as regards the prosperity of the colony, it must be considered rather as an impediment to its improvement than an advantage, by diverting the inhabitants from agriculture, demoralizing their habits, and from its enabling them to procure ardent spirits

[334]

with little difficulty, which in too many instances has led to drunkenness, poverty, and loss of health.

A trade from which the island has derived, and will probably continue to receive, considerable benefit, is that of supplying Newfoundland with schooners for the seal and cod fisheries, black cattle, sheep, hogs, poultry, oats, potatoes, turnips, &c.; the returns for which are made either in money, West India produce, or such other articles as may best answer. Agricultural produce is also exported to Halifax, Miramichi, and other places in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Beef, pork, sheep, hams, cheese, oats, potatoes, flour, and fish, are occasionally exported to Bermuda.